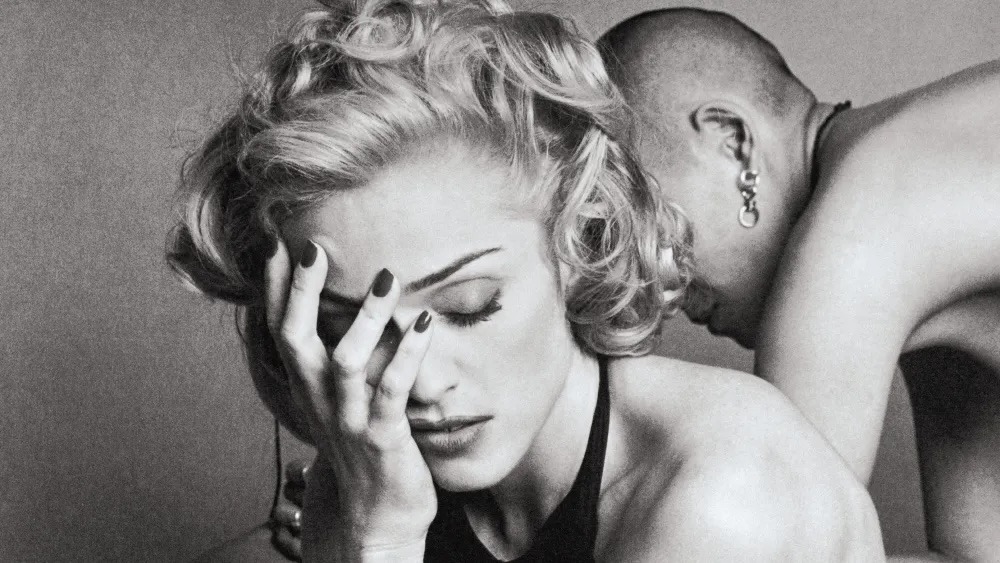

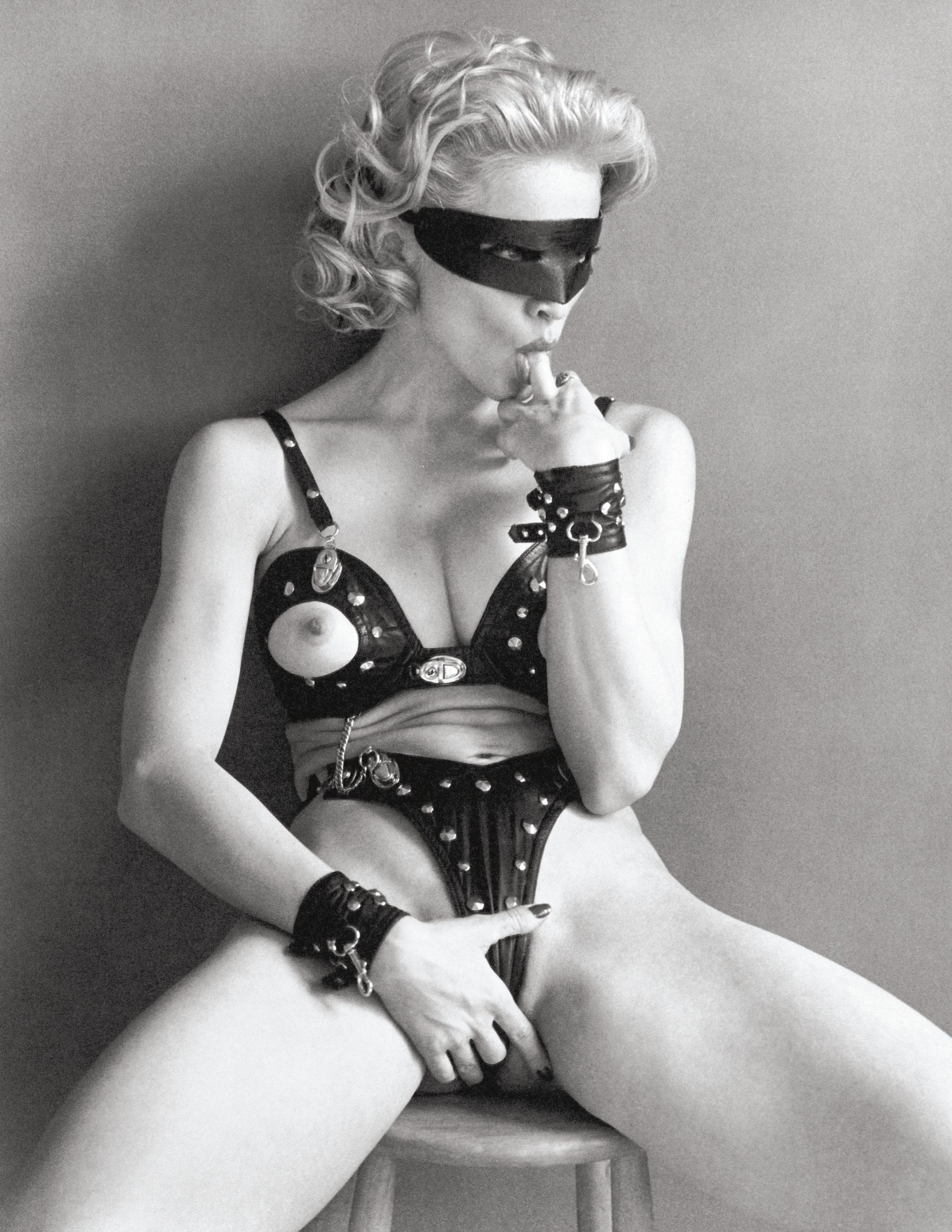

SEX BY MADONNA AND STEVEN MEISEL

In “Sex”, Madonna boldly deconstructs stereotypical representations of women, which according to Nicola McCartney’s “Gender, Sex & Sexuality” (2025) lecture, revolved around being perceived as “fragile, passive, weak, and emotional.” In the book, Madonna adopts both hyper-fem and masculine personas. She adopts the moniker ‘Mistress Dita’, inspired by the German actress Dita Parlo, and can be seen in one photo, sitting delicately on a chaise lounge, dressed in white lingerie, with an older man fondling her breasts — a stereotypical representation of femininity; she’s delicate, meek, and perhaps overpowered. But in other photos, she’s adorned in BDSM gear, one in particular shows her whipping a man, who’s bent over. Judith Butler’s Gender Performativity theory suggests that gender is a performance, as opposed to a binary state. As touched upon by McCartney, Butler proposes the question: “How do certain sexual practices compel the question: what is a woman, what is a man?” (Butler, J. 1990). Butler suggests that inherently, sexuality and its practices are not bound by the societal construct of gender, and Madonna embraces this idea. She’s multifaceted: both delicate and dominant. Additionally in her “Gender, Sex & Sexuality” lecture, McCartney explores the impact that dress may have on our gender performance, for instance, a poster at Adekunle Ajasin university, prompting girls to dress more conservatively to “stop provoking sexual harassment”. In “Sex” , Madonna embraces McCartney’s extension of Judith Butler’s ideas, her gender performance is heavily reliant on the attire she’s wearing — it refuses to fit into a single binary.

In Marlon Bailey’s “Gender/Racial Realness” essay, they explore the role performance plays in ballroom culture, as well as how it’s impacted and interacted with general society; in particular, society’s views towards femininity and sexuality (Bailey, M. 2011). Bailey suggests that in ballroom culture, “the terms ‘cunt’ and ‘pussy’ refer to ultimate femininity”, a subversion of how the term has typically been used in society, as often derogatory and insulting, or weak. Bailey continues, citing, “although in popular culture, cunt and pussy are deployed in a derogatory sense and may seem inherently misogynistic — reclaiming the definition, going against the misogynistic”. This is reflected in “Sex”, in an excerpt structured as a hand-written letter sent to a man called ‘Johnny’, she refers to her vagina as her “pussy” and “cunt” colloquially (Madonna, 1992), reclaiming the derogatory, misogynistic connotations the terms have become associated with. As Bailey claimed, when Madonna refers to her vagina with such terms, it’s the mark of “ultimate femininity” (Bailey, M. 2011). She’s directly talking to the oppressor, and reclaiming a derogatory term back. In the same way that Bailey talks of how ballroom culture provides a sense of identity to young queer people of colour, Madonna’s reclamation of ‘cunt’ and ‘pussy’ solidify her own concept of femininity and what it means to her.

Furthermore, “Sex” by Madonna saw the singer position herself as a being opposed to the normative constraints of 90s society. HIV/AIDs was near its peak in 1992, being cited as the gay “plague” and “virus”, causing public hysteria surrounding the LGBTQ+ community. Being surrounded by gay creatives all her life, such as Jean-Baptiste Mondino and Steven Meisel (the coffee-table book’s photographer), Madonna’s allyship is hardly surprising, but that doesn’t make it all the less bold, especially given the social climate surrounding sexuality. “Sex” features multiple images depicting homoeroticism and gay sexual acts, with gay porn stars featuring in the book. Madonna herself partakes in acts of bisexuality, sexually suggestively posing with model Naomi Campbell, and talking of sexual desire towards a woman named Ingrid. In their “Disciplinary Regimes” essays, Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas claim that “here was Madonna, during the time of AIDs, revelling in bestiality, sadomasochism, lesbianism, and bondage”, (Geczy, A. and Karaminas, V. (2020)) and parallel a quote attributed to Michael Foucault: “the overwhelming, the unspeakable, the stupefying, the ecstatic, a pure violence and wordless gesture”. Geczy and Karaminas liken the “Sex” book to an art piece that challenges and exceeds societal bounds, so much so that it’s almost an “unspeakable” event, heightened by the political landscape of the 90s. In her “The Body” lecture, McCartney (2025) touched on Foucault’s ideas surrounding the Panopticon, and how its inmates are “caught up in a power situation of which they are themselves the bearers”, (Foucault, M. 1977) which, in the context of “Sex”, suggest that women are responsible and contribute to their own docility and submissiveness — which Madonna fiercely denounces with the power she possesses throughout the book.. Here, Foucault suggests that society add to their own docility, and that their lack of power ends up becoming internalised within themselves. However, the “Sex” book actively fights against this, Madonna is anything but docile to society’s constraints, instead, actively fighting against them.

In Tynan J’s essay, “Michael Foucault: Fashioning the Body Politics”, (Tynan. J, 2019) he suggests that “fashion is one of the technologies through which power regulates the body, shaping it to the norms of gender, class, and race.” Tynan continues, claiming that “the regulation of sexuality is integral to the constriction of gender subjectivity and the maintenance of social order”, referring to how society regulates and restricts sexual behaviours, concepts, and identities. However, “Sex” completely subverts this idea: acting almost as a tool of rebellion against societal norms, embracing taboos such as bisexuality, voyeurism and S&M. The power of a star like Madonna also bared resonance to society, as Kirsten Marthe Lentz puts it, “Madonna’s mainstreaming of gay images has great liberators potential and encourages mass acceptance of homosexuality.” (Marthe Lentz, K. 1993) While Madonna does arguably carry a sense of power greater than your ordinary citizen, she’s not using her platform to enforce societal constraints, instead, acting as a guerrilla, with a book that acted as a source of rebellion against binaries of gender and sexuality.

In her “Visuality & The Gaze” lecture, Dr. Christin Yu expands on Laura Mulvey’s concept of “The Male Gaze” (L, Mulvey. 1975). The male gaze refers to patriarchy being reinforced in Hollywood, where audiences are assumed as a heterosexual male viewing subject — in addition to the audience identifying with the male character on the screen. D. Fuss also introduces the concept of “homospectorial viewing” (Fuss, D. 1992) within female fashion photography, where a heterosexual audience is also assumed, but also how women, in McCartney’s words, were “forced to consume, in a voyeuristic if not vampiristic fashion, the images of other women.” However, “Sex” denounces this theory on a myriad of different levels. Firstly, the book subverts the “male gaze theory” as Madonna is seen as both a desirable woman, but also a woman who’s fully in control of her sexuality, both in the book and in real life. Madonna had full creative control over the book, even through teamwork with her longtime collaborator, Steven Meisel. Mulvey claims that, through the male gaze, “in a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active male and passive female”, but in “Sex”, more often than not, Madonna is seen completely in control. Additionally, the case of homospectorial viewing isn’t applicable towards “Sex.” Steven Meisel, a gay photographer, rarely presents Madonna, or the book’s other guests, as objects of sexual desire catered for a heterosexual viewer. Scenes of BDSM and bisexuality hardly appealed to the average 90s citizen who would’ve been a so-called, “homospectorial viewer.” Furthermore, many of Madonna’s fans were gay men, with Marthe Lentz noting that, “Madonna’s ‘safe’ bisexual persona is a matter of cross-audience appeal, a clever marketing ploy”, (Marthe Lentz, K. 1993) once again suggesting that Madonna is in control of the narrative she yearns to create. Madonna reclaims what it means to be a femme fatale, a character that Mary Ann Douglas suggests is, “a projection of masculine insecurities and should not be viewed as a character with agency.” But once again, “Sex” denounces this, Madonna, in fact, had the most agency when it came to the book, rarely in the book is she ever portrayed as a character with zero agency at all — and would end up including the lyric, “can’t have the femme without the fatale” in her 2005 song, “Like it or Not.” Additionally, Gary Burns argues that in many of Madonna’s performances, she “simultaneously spoofed sluttification and was the apotheosis of it”, (Burns, G. 2006) she embraced both the idea of being an erotic symbol, but also ridiculed it.

In conclusion, as exemplified through theoretical viewpoints and supporting evidence, the “Sex” book is undoubtedly a cultural landmark within the realm of what a pop star was capable of. The coffee-table book actively subverted stereotypes surrounding gender, sex, and sexuality; and the result sees Madonna presented as a multi-faceted, powerful, and inclusive woman.